Save local U.S newspapers

February 10, 2020

In 2019, Youngstown, Ohio’s newspaper, The Vindicator, announced its closing. Eulogizing the paper, Joel Kaplan, associate dean of Syracuse University’s Newhouse, said: “Democracy, as we know it, is about to die in Youngstown.” Compelling evidence backs Kaplan’s prediction. When the Cincinnati Post, the Rocky Mountain News, and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer closed, civic participation declined in their respective counties, and voters became less likely to cross party lines.

Papers like The Vindicator foster civil discourse and engagement with local issues that result in polarized groups finding common ground. As the U.S. enters the 2020 presidential election, the decline of local newsrooms threatens its democracy.

With local publications disappearing, Americans turn to national organizations. However, people curate their news diets with predispositions. Information perceived as accurate reinforces existing political beliefs. After a study on media polarization, the Pew Research Center concluded that between liberals and conservatives, “there is little overlap in the news sources they turn to and trust.” Politics also shape the parameters of relationships and social circles. Ideological stagnancy forms in the dearth of political conversation between dissimilar groups.

National news does not provide insight into local affairs either. With neither the interest nor ability to cover specific counties, such outlets focus on sensational ‘hot button’ topics. General news prompts consumers to consider problems like immigration, gun control, or in 2020, the impeachment of Donald Trump, while neighborhood issues are underreported.

Slanted takes on divisive issues broaden the distance between antithetical views. On the contrary, local issues, reported by local papers, promote discussions. When the Tampa Bay Times reported on their community’s failing school system, political differences did not stop Democrats and Republicans from a conversation on reform. In the interest of thoughtful communication that bridges the party divide, during the 2020 presidential election, it is essential to move beyond static dialogue.

To have larger discourse on politics and democracy, the conversation must first return, quite literally, to common ground. Americans should consider how a candidate represents their region, not on abstracted debates, but on problems pertinent to everyday circumstances, such as education, infrastructure, or the opiate crisis. When talking points are founded in daily life, disengaged citizens may find themselves entering political conversations as well. At their best, local newspapers spark discourse while also serving as a forum of debate.

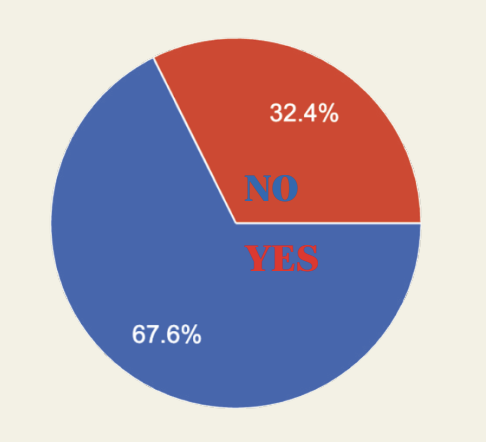

As papers go bankrupt, local journalism faces the threat of collapse. In the U.S., 225 counties are without a paper, and half of all counties – 1528 – have only one. Many of those papers are understaffed and fail to provide adequate coverage. With a divided country entering an election cycle, civil discourse is imperative to electing a candidate that represents a broader American consensus. To begin repairing social division, the local press should adopt resourceful solutions to fit into the media’s digital frontier. To defy Kaplan’s prediction on the future of democracy, throughout all of the U.S., there must be an effort to save local journalism.