History department teaches social justice

The History department has incorporated new texts in their curriculum, such as Nancy Isenberg’s “White Trash” and Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s “An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States” in an effort to teach diverse perspectives.

November 16, 2020

Protests against systemic racism this summer have only deepened Friends Seminary’s commitment to teaching social justice through history. Part of Friends’ mission as a Quaker school is to turn students into citizens who can help “bring about the world that ought to be.” This mission is firmly rooted in social justice, which can broadly be defined as the concept that everyone in society should have fair access to opportunities and privileges of all kinds. Both the History Department and CPEJ have clearly taken on the mission to teach social justice to students.

In the past ten years, Friends has created the Center for Peace, Equity, and Justice, or CPEJ. According to the Friends website, CPEJ aims to “connect ideas, resources, and people to advance social justice, build inclusive and sustainable communities, and foster lifelong commitments to public service.” This year, as COVID-19 prevents many traditional service events from being held, CPEJ has introduced service learning modules. These modules, posted on PowerSchool, allow students to learn more about particular issues through media such as videos, articles, and discussions. The modules use the Head, Hearts, and Hands model of service. This model emphasizes the importance of using our hearts to build empathy for others and our heads to build understanding of an issue, along with taking direct action with our hands.

Kimby Heil, Director of Service Learning and Civic Engagement at Friends, argues that teaching history is an integral part of CPEJ’s mission to further student awareness of social justice issues, using the Head, Hearts, and Hands model. According to Heil, if people do not understand the history of the issues they care about, they cannot truly engage with these issues on a deeper level. “When you think about social justice as fighting for something that’s right by getting to the root of a problem, if you’re using that lens, then history helps us understand the root of the problem,” Heil said.

Jason Craige Harris, Director of Diversity and Inclusion at Friends, also sees history as tied to social justice. He added, “In U.S. public life, we are seeing stories told about the past that are inaccurate and ideologically driven. The kind of critical questioning students are learning to do in the History Department is essential for good citizenship.”

Like CPEJ, the History Department at Friends also has increased its commitment to using history to create socially engaged citizens. Bram Hubbell, who has taught history at Friends for 20 years, sees the way he teaches history as tied to the practice of empathy. According to Hubbell, when students don’t look beyond the history of Europe, they lose the ability to see someone else’s perspective. Hubbell argues that this ability to relate to other people is essential to being an active citizen.“When you look at the world today, in terms of understanding the Black Lives Matter protests or the issues that are at stake in our elections, it’s really between people who are trying to understand how someone else experiences the same event, and people who want to impose their own monolithic vision,” Hubbell said.

Hubbell’s sense of the importance of looking at multiple perspectives in the past helps explain the History Department’s efforts to include diverse voices. Hubbell has recently moved to a new textbook for his 10th grade world history class, as he wanted a textbook that centered the most diverse group of voices possible. He also has increased his efforts to find primary sources from multiple groups of people, not just European men. Since his second year at Friends, he has used his travel narrative assignments as a way for students to use primary sources to write from the perspectives of different voices in history. According to Hubbell, these assignments are designed to allow students to build empathy by putting themselves into the shoes of another person.

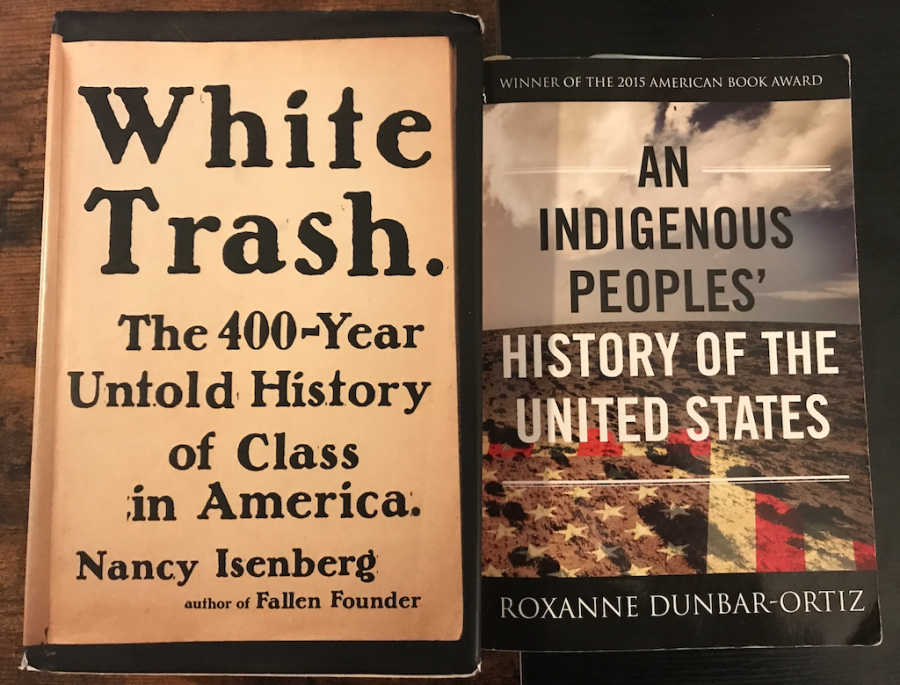

Stefan Stawnychy, chair of the History Department and AP US History teacher, has also worked to include diverse perspectives in the classroom. For example, he has assigned students readings from texts such as An Indigenous People’s History of the United States and White Trash: the 400 Year-Old Untold History of Class in America.

Susannah Walker, another History teacher, has moved away entirely from using a textbook in her US History class, instead using a series of narratives created by her and her colleagues at a previous school. According to Walker, her US History course “was explicitly designed to allow us to bring in many more different kinds of voices in the form of primary sources and secondary sources that could both illuminate voices from the past, but also illuminate different perspectives on history from historians.” For example, this year, while teaching students about the American Revolution, she has included a class focused on African-Americans in the Revolution, and another that focused on women in the Revolution. However, Walker does not see the inclusion of these perspectives as just part of a mission of social justice. She also sees these voices as an integral part of US History as a whole.

The History Department’s interest in diverse groups of people has also informed its decision to move away from offering any AP History courses. Hubbell, who was on the committee that wrote the AP World History curriculum for the AP office, introduced AP World History to Friends and taught it for about ten years. However, he ultimately decided to end the course because of how much focus it forced him to put on specific facts and dates.

Stawnychy gave similar reasoning when explaining the school’s decision to no longer offer AP US History after this year. According to Stawnychy, when the school stops offering AP US History, “we can have that additional time that we need to really dive deep into things like Indigenous issues, things like the Black experience, things like the experience of women throughout history, as opposed to constantly having to balance those more social justice lenses.” Walker, who used to be a reader for the AP US History exam, added that in many AP US History courses, “you’re reading a huge, thick, college level textbook, and you’re drilling on all the multiple choice on the tests, and you’re doing all this practicing, and it’s hard to make space necessarily for having deeper conversations about the primary sources.”

The History Department’s classes have also been recently impacted by current events, specifically racial justice protests. Walker made the decision this summer to foreground race in her US History class even more than usual, due to the Black Lives Matter protests. Hubbell has discussed Black Lives Matter protests around the world in his World History class, and Stawnychy plans to address the BLM protests in his Power, Politics, and Citizenship elective when they begin looking at revolutionary movements. However, according to Stawnychy, these protests did not prompt any large scale change in the department, as it had already been making meaningful effort to engage with issues of racial justice. He attributes this effort to the work of CPEJ, which has partnered with the History Department to make it aware of what needed to be added to the curriculum to make it as inclusive as possible.

Some recent changes in the History Department have also come about as the result of students themselves. Hubbell’s decision to try to find more primary sources written by women was prompted by a student about seven years ago who commented on how few female voices they were reading. The history electives that the school offers each year are also impacted by student interest levels. For example, Stawynchy’s politics elective is offered thanks to students petitioning to have it included.

Magnifying student voices is an important part of the History Department’s work, not only in terms of curriculum, but also in terms of discussions in class. Stawnychy is open about his own left-leaning political views, but he also has taught students who are self-identified conservatives. “I think it’s important for me, particularly since I teach politics, to be upfront with where I am politically, but to also attempt to create an environment that’s conducive to not shutting out those alternative perspectives,” Stawnychy said.

In CPEJ discussions as well as the fifth and sixth grade goLEAD service-learning courses she teaches, Heil uses tools like reflection questions and ground rules to help students feel comfortable disagreeing. These strategies ensure that “it’s less about pushing an agenda and more about trying to help students tap into their own sense of morality and justice,” Heil said.

The History Department’s emphasis on giving students critical thinking skills and teaching them about various perspectives is tied to Friends’ goals as a Quaker school. Friends’ website states that the History curriculum “reflects a commitment to Quaker values such as the worth of every individual and the quest for social justice. Through the curricular offerings, students are encouraged to value diversity and inclusivity.” Hubbell connects his teaching of history to the Quaker SPICES of Simplicity, Peace, Integrity, Community, Equality, and Stewardship. According to Hubbell, “as teachers, we really should try to figure out how we can do things that most lean into that in a way that isn’t just surface or superficial, meaningfully engage these questions and the values, and use the faith and practice as a guide.”