After almost three years without water fountains (due to Covid), Friends has recently reinstalled the glorious machines. Despite gratefully spraying the water into their mouths from the fountains, many students don’t know where their drinking water comes from.

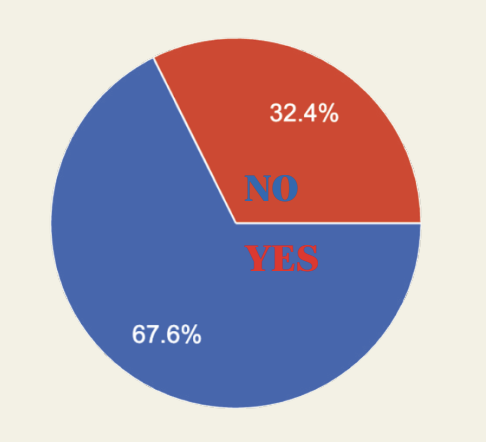

I recently conducted a survey, asking students in the hallways, “Where do you think New York City water comes from?”

I received varying answers. One student confidently asserted, “The ocean.” Another was less sure, “Maine?” A third candidly replied, “I have no clue.”

The right answer is not Maine or any ocean; it is the 19 reservoirs and three controlled lakes that span across a 2,000-square-mile watershed in portions of the Hudson Valley and the Catskill Mountains. This vast water supply system took years to build and relocated thousands of people.

In the 1600s, as New York City’s population began to grow exponentially, so did the need for water. The city constructed public wells and a local reservoir, but it wasn’t enough. Fires took out whole blocks, unable to be combated because of limited water accessibility. Increases in population and manufacturing activity also led to major water pollution. The city urgently searched for an answer, and in 1884, the state legislature allowed NYC to explore areas outside of the city’s boundaries for a clean water source.

City officials decided that Croton, a rural area 40 miles from the city, would be the perfect place to create a waterway to the city. Due to the urgent need, New York State allowed the city to take over Croton and use eminent domain to force all residents to relocate. Construction of the waterway began in 1837, and workers built a masonry dam that could hold 600 million gallons of water, an aqueduct, and receiving and distributing reservoirs in the middle of the city. On July 4, 1842, fresh water finally flowed from Croton into Manhattan.

Following the successful creation of the Croton system, NYC introduced five additional reservoirs, but by the early 1900s, those six reservoirs still weren’t producing enough water to meet demand. City officials realized they could use the polluted Hudson River to satisfy water needs if they accessed it at a point before contamination in the Catskill Mountains.

In 1907, the City began construction of the Ashokan Reservoir and then the Schoharie Reservoir in the Catskills; the two of them were finished in 1928. To this day, they provide the city with 40% of its water.

The final addition to NYC’s current water system was the Delaware aqueduct. It was completed in 1944, stretches 105 miles, and combines four other reservoirs.

Although the success of upstate New York’s reservoirs is undeniable, their construction cost a great deal for many people. In total, 24 towns, villages, and hamlets were flooded, destroying communities and forcing people to rebuild their lives elsewhere.

“Today, upstate New York would never agree to something like this,” explained Don Myers, a consultant for the Catskill Water Discovery Center, to The Insight.

Myers was quick to point out though that the City is responsible for the complete cost of the system. “The city pays millions for the protection of our water … The inspecting, protecting, transportation. The entire system was built with city money.”

Looking ahead, aging infrastructure and leakages may prove troublesome to the water system. The city recently began construction of a 2.5-mile bypass to correct a leak in the Delaware aqueduct, but the project is running two years behind schedule.

The water spouting from the water fountain does not magically appear. Next time you are taking a sip, remember the labor of all those people who built the century-old waterway system and that it traveled nearly 100 miles to get to you.