Beatrice Moyers ’21 recommends ten books

Beatrice Moyers ’21 shares ten books – ranging from classics to contemporary best sellers – she read this past year.

February 8, 2021

The ten books I enjoyed the most in the past year all provided some sort of distraction during months of monotony. Some forced me to examine systemic problems that would have otherwise been all too easy to ignore. Others provided insight into the past, an alternate reality to absorb myself in, or simply interesting information. Each of the following ten books deserve to be read (and to be purchased from independent bookstores!). This list includes five fiction and five non-fiction books, in no particular order.

Fiction

“The Western Wind, ” by Samantha Harvey

At first glance, this novel may seem a bit intimidating – it’s the story of a 15th century priest in a small village, told in reverse chronological order. But Harvey manages to make people living far in the past seem vivid. It tells the story of a priest who struggles to keep his small parish engaged, raising questions about the role of organized religion in individuals’ faith. It’s also a murder mystery, opening with the news that the wealthiest man in the village has drowned. “The Western Wind” doesn’t shy away from sometimes-gruesome depictions of medieval life: stinky animal skin masks, instruments made from the innards of a sheep, the corpse of a dog. The specificity of these descriptions prevents the book from just seeming like a period piece – you can’t help but get drawn into the world Harvey creates.

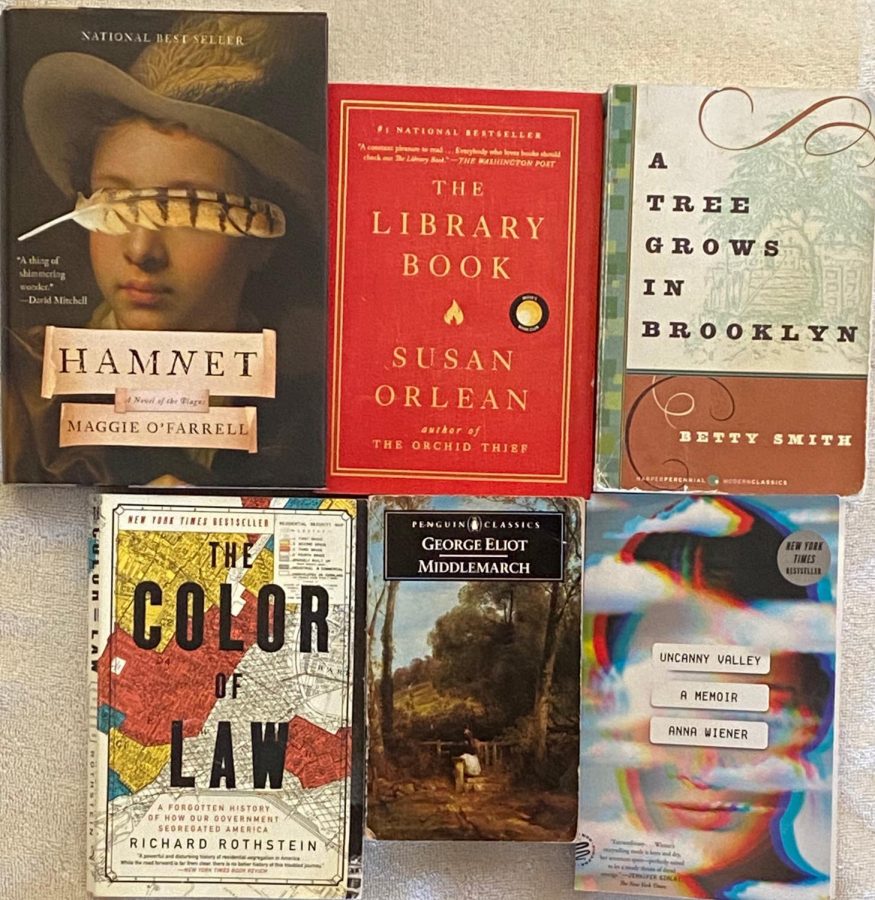

“Middlemarch,” by George Eliot

Yes, “Middlemarch” is a classic published 150 years ago, but it’s anything but a dusty relic. It’s a classic for a reason. It manages to have lots of characters, each fully defined in their own right: A banker who wants to escape his unsavory past, a scholar struggling to find his own ideas, a doctor frustrated by the slow pace of change in the medical world, a young woman both confident in her beliefs and in need of validation from other people. If you want a book that’s a look into 19th century politics, a romance, a social satire, and a page turner, “Middlemarch” is a great choice.

“Rodham,” by Curtis Sittenfeld

“Rodham” attempts to answer the question: “What would have happened to Hillary Clinton if she had never married?” In its early chapters, this book mirrors Clinton’s own biography, but it includes emotion that a politician would never actually express openly. Later, the book becomes a look at an alternate reality, in which Hillary becomes a law professor at Northwestern, and she and Bill run against each other for president. “Rodham” accomplishes the impressive feat of making a person who is instantly recognizable into an actual human being, while not losing sight of that human’s impact on the world around her.

“Hamnet,” by Maggie O’Farrell

Set in the late 16th century, this book tells the story of William Shakespeare’s son, Hamnet, who died a few years before Shakespeare wrote the play “Hamlet.” It juxtaposes Hamnet’s death with Shakespeare’s relationship with his wife, Agnes, an unconventional woman who can perceive things in others they might wish remained hidden. “Hamnet” manages to make Shakespeare the least interesting of its characters, bringing often overlooked figures of the past to light. It’s also a study of grief and how we deal with it– it’s worth reading for the final scene alone, in which we see the connection between “Hamlet”the play and Hamnet the son.

“A Tree Grows in Brooklyn,” by Betty Smith

I first read this book when I was about 10 years old, and I’ve come back to it every few years since. It remains magical because it paints a somewhat nostalgic picture of Brooklyn in the early 20th century, but it doesn’t let that nostalgia get in the way of honesty. As we watch the main character, Francie Nolan, grow up, we get a clear-eyed view of her father’s alcoholism, but we don’t lose the qualities that make him lovable. We get an assessment of the poverty of Brooklyn’s inhabitants, but we still understand the borough’s charm. “A Tree Grows in Brooklyn” is one of the rare books equally suited for children and adults.

Non-fiction

“The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration,” by Isabel Wilkerson

The Great Migration – the migration of millions of Black Americans from the South to northern cities between roughly 1916 and 1970 – is sometimes overlooked in the study of important historical events. But the exodus of many Black southerners to northern cities profoundly shaped America, as Isabel Wilkerson argues. The three migrants Wilkerson chooses to focus on, all from different times and backgrounds, are not just statistics, but rather actual people that I grew to care about over the course of the book. The blend of empathy and history in “The Warmth of Other Suns” makes it great.

“The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America,” by Richard Rothstein

If you want to have a better understanding of what the phrase “systemic racism” really means, this book would be a great starting point. The book provides a sharp assessment of the role that the government has played in neighborhood segregation. “The Color of Law” systematically dismantles the argument that housing disparities across race lines just happened because of individual whims. The book outlines how official policies ranging from redlining to segregation in public housing still impact our communities today. In doing so, it demonstrates the pull that past policy still has on our present-day lives, and the need for our government to address that past.

“Uncanny Valley: A Memoir,” by Anna Wiener

In “Uncanny Valley,” Anna Wiener recounts working in the tech industry in San Francisco after leaving a dead-end job in book publishing. She gives insight into the tech boom, offering a perspective that only someone who is both an insider and an outsider could provide. The book demonstrates the appeal of an industry that prides itself on innovation. At the same time, it shows the danger of the constant search for optimization at the expense of actual people. Wiener’s snarky wit makes her book a poignant and occasionally funny depiction of a city, and a world, being transformed by techno-utopians.

The Library Book, by Susan Orlean

I read this book in March of 2020, when I had just entered quarantine and had no idea what was going to happen next. This book was a balm for anxious times – both an ode to the wonder of public libraries, and an account of the mysterious fire that almost destroyed the Los Angeles Public Library. “The Library Book” is a reminder to appreciate the underappreciated: libraries, and the people who devote their lives to them. It’s especially poignant to read this book of appreciation now, when public spaces like libraries seem like relics of the distant past.

“A Promised Land,” by Barack Obama

I know… you’ve probably already heard of this book, and it’s been on countless “Best of 2020” lists. But “A Promised Land” is worth the hype. Obama devotes a lot of page space to explaining issues that can be confusing: subprime mortgages, complex climate negotiations, health care policy. His devotion to explaining these issues and the choices he and his cabinet made in full detail (the book is over 700 pages!) is what makes this book so engaging. “A Promised Land” provides a clear picture of what a politician actually does every day, and the compromises that even the most idealistic public figures are pushed to make.