Dave Isay: Listening is an act of love

October 20, 2018

Dave Isay graduated from Friends Seminary in 1983. 20 years after graduating, Isay founded StoryCorps, a nonprofit organization that provides a platform for people to learn others’ life stories. In booths around the country, skilled StoryCorps facilitators provide the means for two people to record an interview, some of which are broadcast on NPR. StoryCorps also has a MobileBooth, a trailer which travels around the country to help people conduct interviews. All of the interviews StoryCorps collects are housed in the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress. A one million dollar prize from TED Talks has even funded a StoryCorps mobile app, which allows anyone to record a meaningful conversation and upload the audio to the Library of Congress and StoryCorps.me platform. Since its creation 15 years ago, StoryCorps has told the stories of a quarter million Americans. The Insight talked with Isay to learn more about the philosophy behind StoryCorps and how his experience at Friends led him to become committed to sharing the stories of ordinary people.

THE INSIGHT: Did you know that you were interested in telling people’s stories right after college? When did you become interested in radio?

DAVE ISAY: When I got out of college, I was supposed to go to medical school and then, through a series of weird events over 24 hours, I ended up doing a story about ten blocks away from Friends. Actually, what happened is I met a couple. I was heading to medical school, but I was taking a year off and tutoring people because part of me knew I wasn’t doing what I was meant to do. As I was walking around the East Village, it was 7th Street between 1st and A, I came across this store that was just a little storefront. The windows caught my eye, and I went in. I started talking to the people who ran it. It was a couple, and his name was Angel and her name was Carmen. I started talking to them, and it turned out that they were recovering heroin addicts who had AIDS, and this was 1987, so that meant that AIDS was a death sentence. They took me to the back of their shop, a little tiny shop, and they had built this model to a museum of addiction that they thought they were going to build before they died. They showed me all these letters they had gotten, they had written to Donald Trump and everybody else asking for funding. They got replies that were just standard replies, and of course they weren’t going to get funding, but they had hope in the letters that maybe they would. I was just really blown away by their courage of conviction; they were just these amazing people. I went home, and I started calling all the stations and saying, “you should do a story about this couple who wants to build this museum before they die.” And everybody said no. And then I started calling the radio stations. And everyone said no, except I got to one radio station, WBAI, and a woman named Amy Goodman who’s pretty famous now, she does a show called Democracy Now, picked up the phone and said “It sounds like a good story. Why don’t you do it yourself ?” So I took a tape recorder and interviewed them. When I started recording, I knew that this was what I was going to do for the rest of my life. I then went back and put it on the radio, Amy helped me to put it on the radio. Someone from NPR happened to be driving through town and heard it and picked it up for NPR. So I dropped out of medical school that day, and my fate was sealed.

I know you’ve also done some documentary work.

Radio documentaries, yeah, that’s what I did for decades. That’s what I did for a long time before starting StoryCorps.

You said in an interview that “StoryCorps is the opposite of the documentary work I used to do.” Could you elaborate on that?

It kind of takes documentary and turns it on its head because documentary work, when I used to do radio documentaries, you’d interview a few people to create this work that’s heard by many, many people. That’s the purpose of it. And that’s documentary work, if it’s film, or if you’re writing it, or whatever, you do some interviews or take some pictures, and then you share it broadly. The idea with StoryCorps was to say that the final product actually doesn’t matter, but we want to give as many people as possible the chance to be listened to. It’s really the listening part, the chance to be interviewed, that’s what’s StoryCorps is all about. The stories that come out of it are secondary. So, it’s the reverse of traditional documentary.

It says on the StoryCorps website that your goal is “to teach the value of listening, and to weave into the fabric of our culture the understanding that everyone’s story matters.” Could you talk a little bit about how listening can build bonds between people? Was that something you were aware of from a young age or was that more of an epiphany moment?

When I was a kid, I was kind of a weird kid. I was more interested in spending time with older people than people my age. I spent a lot of time listening when I was a kid, but I wasn’t really conscious of it. When I did radio documentaries for the twenty years before starting StoryCorps, when I did interviews on death row when I was 23 years old, I saw that just listening to these guys talk about their lives, not just about their crime, and their dreams for their kids and who their parents were, that it was important and sometimes transformative in their lives. I realized how important it is for people, especially people who might feel like their stories don’t matter. You look at the criminal justice system, everything about the criminal justice system is geared towards telling people that their life has no value. But sitting and listening to them and asking them questions and giving them a chance to reflect on their lives and leave a legacy is the opposite of that. So, I realized that listening can be incredibly powerful. And the first book I did with my editor, I think he named it Listening is an Act of Love, and that sort of sums it up.

Listening is a really important part of Quaker meeting. We all sit in silence and listen to people speak out of it. When you were in high school, did that experience move you at all? Were you interested in Quaker meeting?

It didn’t move me at all. I came to Friends in eleventh and twelfth grade. But it had a huge influence in starting StoryCorps. With some of these things you don’t realize at the moment, but later on you do. I came to Friends in eleventh grade, I had no friends, and it was kind of a tough move, I was a weird kid. By twelfth grade, it was actually much better. Friends really was transformative for me. Back when I went to Friends, Friends was a school for people who had gotten kicked out of other schools. It’s not like that anymore. I had no confidence at all. And by the time I left Friends, I actually had hope. And silent meeting, I was just too self-conscious to connect to what was happening, it didn’t make sense to me. But it was somehow kind of ingrained in me. And I think that StoryCorps has really in many ways grown out of that experience. I owe a huge debt of gratitude. I think there’s a guy named Parker Palmer, who’s a well-know Quaker writer, who’s had a huge influence on me in my thinking about StoryCorps, so I feel like Quakerism is really baked into the DNA of StoryCorps, and that all comes from my time at Friends. I didn’t know it at the time. So that’s a good lesson, that sometimes things happen to you, and you don’t realize how important they are until later.

.

The Quaker meetinghouse is thought of as a sacred space where you can speak without judgement. Do you feel that a StoryCorps booth is kind of like a meetinghouse in that way?

It is, I hadn’t really thought about that. Everything’s changed at Friends since I went there except Mr. Byrne who wasn’t a teacher of mine, but I think he’s the only teacher who is there from when I was there. But my nephew got bar mitzvahed there, and the meetinghouse is exactly the same. But I never thought of that, the idea that it’s a sacred space where you have the freedom to say whatever it is you want to say. But, I think that it is very similar in that way. When I talked about the elements that are baked into StoryCorps, that idea of being in a sacred space, and the microphone giving you the license to talk about things you don’t normally get to talk about, are key, just like the Library of Congress piece.

You launched the StoryCorps app three years ago. When you launched it, did you have any concern about what would happen with no facilitator for an interview? Did those concerns turn out to be true?

I was extremely concerned. I was concerned when StoryCorps launched. 14 years ago, when it launched, I didn’t know what was going to happen, I didn’t know if people were going to do crazy things, kill each other in the booth. Like Jerry Springer kind of things, shoot each other for revealing crazy stuff. And that never happened. With the app, I was concerned that people were going to abuse the app, I didn’t know if people would get it. And one of the best moments of the last 14 years was after we launched the app, the first moment that I had quiet, I was in a car. I was able to start listening to what was coming in on the app, and I heard that people were doing it with complete fidelity to StoryCorps. It was the first unfacilitated interview ever. A lot of the interviews that were coming in, I don’t know how they heard about it, people who had never heard of StoryCorps, never heard of public radio, in small towns in Texas or the Appalachia. The interviews were much shorter than typical StoryCorps interviews, the signature StoryCorps interview which happens in the booth is 40 minutes. The average app interview is about ten, eleven minutes. But it was completely in the spirit of how a StoryCorps interview happens. People who had never heard of StoryCorps picked it up and were able to do this really perfectly. I think it speaks to one of the lessons when the facilitators come back, when they come back from recording stories and bearing witness to all these stories and you ask them what they learned, they all have a variation of that Anne Frank line, that people are basically good. And I think that’s one of the important lessons of StoryCorps, the basic goodness of people, no matter what their politics are, where they come from, their socio-economic status. We really do share so much more in common than divides us.

You also have a lot of initiatives that are focused on telling the groups of stories of particular people. Do you pick the people you highlight based on current events?

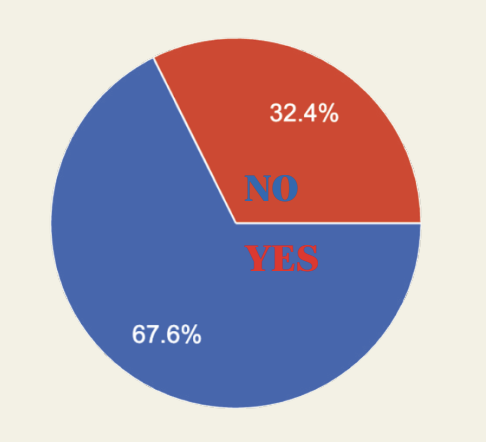

Sometimes. We’ve had, I think, a dozen big special initiatives, the first was with 9/11 families. We had an African American initiative, a Latino initiate, an LGBT initiative which focused on people born before Stonewall, a military initiative. It’s kind of a combination of stories that need to be told and where we can find funding. And we’ll continue to do that. Our newest initiative [One Small Step], which is a little bit different, is getting people across the political divides who don’t know each other to come to StoryCorps and talk to each other, which is completely new for us.

I was actually going to ask about that initiative. Where did this idea come from, and if the interviews have already started, how are they going ?

We haven’t actually launched yet, we’ve been testing [the initiative has since launched]. And it’s really kind of miraculous to see what happens. I think what happens is StoryCorps brings out, in many ways, the opposite impulses of social media. If social media brings out our biggest asshole, then StoryCorps brings out our best angels. Because people are conscious, they’re speaking to future generations, and they’re kind of constrained in that way from unleashing the worst of what’s inside of them. We’re going to launch in a couple of months, we’ve been doing test interviews. What we’re seeing is really exciting and impressive in terms of how it makes people feel closer together. I think what we’re going for with One Small Step is dealing with the dangerous tribalism in this country. People who we don’t agree with politically, not only don’t we agree with them, but at this point we often think of them as less than human or want them dead. Mother Teresa used to say that we’ve forgotten that we belong to each other. So this is to remind people that they do belong to each other and use StoryCorps to just recognize that someone who you disagree with can also be a human being. That’s all we’re doing, people aren’t talking about politics, none of that. It’s just to take us one step away from the abyss that we’re kind of on the edge of in the country. It’s totally new for us at StoryCorps, we’ve never had people who don’t know each other talking to each other in the booth, we’ve never had people who are in conflict coming to talk. But I had a hunch that this was going to work, and I think that we’re always trying to look at this simple method and put it to its highest and best use. And it seems like, certainly over the last bunch of years, that everything that StoryCorps does helps people feel closer to each other. If the country is more and more feeling so distant from each other, then putting it towards that divide is I think the most important thing that we can do at this moment.

Are you involved at all in the going-ons of Friends Seminary? Does the school still play an active part in your life?

My brother’s on the board, and I have a board member, and one of his kids goes to Friends. I was at Friends last year talking to his class. Whenever Friends asks me to do something, if I can do it within my schedule, I’ll do it. I have a lot of affection for Friends, it took a kid who was kind of broken and helped me get on a path, so I could do what I was meant to do with my life.

Was there a specific teacher who really helped you?

You know, not really. I think it was just the fact that the teachers saw something in me. I didn’t have any obvious strengths in school, just if you were following kind of a testing kind of thing. But there were some teachers who saw that maybe I wasn’t dumb, and that’s a big deal. StoryCorps is very much about hope, it increases hope and decreases fear, I think in everything it does. In many ways, that’s what Friends did for me. It made me less scared of other people, it made me more hopeful. And that was a great gift.

To learn more about StoryCorps, go to https://storycorps.org